Myth Makers: Comic Creators On Black Panther - Part 3

Mar 04, 2018

“Myth Makers: Comic Creators on Black Panther” is a 4-part exploration of Marvel’s Black Panther. Comic creators across five decades provided PREVIEWSworld with insight into their creative journey with the character. Now that we’ve explored the ‘60s and ‘70s, we continue forward into the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s.

You can read part one HERE and part two HERE.

by Troy-Jeffrey Allen

With a nearly $800 million haul at the box office (as of this writing), you could argue that the legend of T’Challa a.k.a. the Black Panther has officially been written. The film, however, is a medley of story ideas amassed over the last 52 years, and building the mythology that would ultimately culminate in the cinematic adaptation was not a straightforward task. As a matter of fact, for the longest time, the character could’ve have been seen as having more of a cult status, which often doomed him to fade, re-emerge, and fade again every few years as a lead character. “Comics are like that,” current Black Panther artist Ken Lashley points out. “Every book has its time in the sun. I remember a time when X-Men went to reprints…when Captain America was not a big seller. It happens.”

By the time the 1980s had rolled around, the Black Panther had gone through two title cancellations. Still, the interconnected aspect of the Marvel Universe demanded that any unfinished business be resolved. And so, in the pages of Marvel Premiere # 51-53 (1979 – 1980), writer Ed Hannigan and artist Jerry Bingham were tasked with concluding an unfinished Ku Klux Klan arc that they had inherited from a previous creative team. Hannigan and Bingham’s time with the character wasn’t limited to tying up loose ends, however. Before they were done, the duo gave Wakanda – Panther’s homeland - a U.S. embassy, officially ending its isolationist streak. They also were the first to tease the idea that Captain America’s trademark shield may be made of vibranium, the metal that originated from Wakanda.

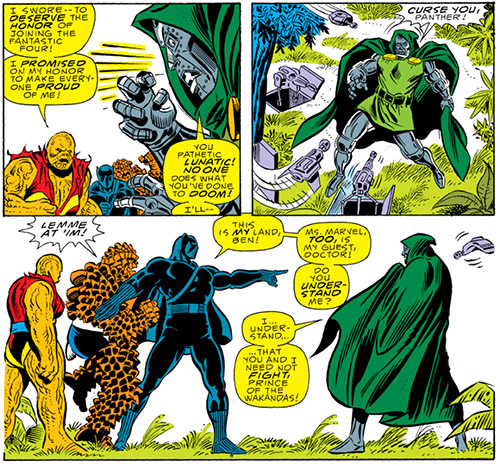

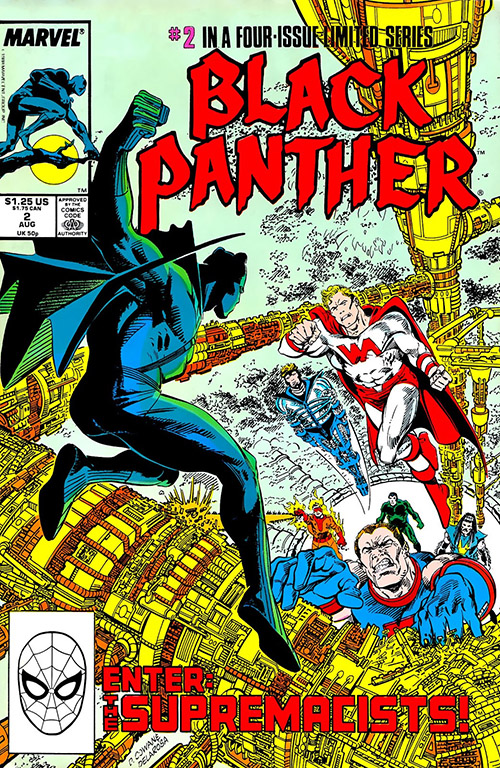

To their credit, other Marvel writers and artists also began looking for opportunities to utilize the Black Panther when a storytelling opportunity presented itself. He continued to make appearances in other books throughout the ‘80s, including (but not limited to) having a chance meeting with the X-Men’s Storm for the “first” time in Marvel Team-Up #100 (1980), butting heads with Prince Namor in a handful of stories, then tackling South Africa’s apartheid in two separate solo adventures in different titles: Black Panther #1-4 (1988) and Marvel Comics Presents #13-37 (1989). The character also displayed equal footing with Doctor Doom in Fantastic Four #311 (1988).

“I became an enthusiast while reading the Christopher Priest run, which was incredibly innovative and compelling,” writer Davis Liss says about discovering the Black Panther. “I’m pretty sure it was while reading Priest I realized just how powerful and compelling the character could be.” Liss would end up writing Black Panther in 2010, but for him, it was writer Christopher Priest’s run starting in 1998 that raised the character’s profile. He’s not alone in that sentiment: “What Priest did with Panther really resonated,” adds current Marvel writer Al Ewing. “It didn’t make any sense that this guy was being second from the left at the back in the Avengers lineup when Doctor Doom was being Doctor Doom. It made absolute and total sense that he was this ultimate ten-steps-ahead super-spy figure.”

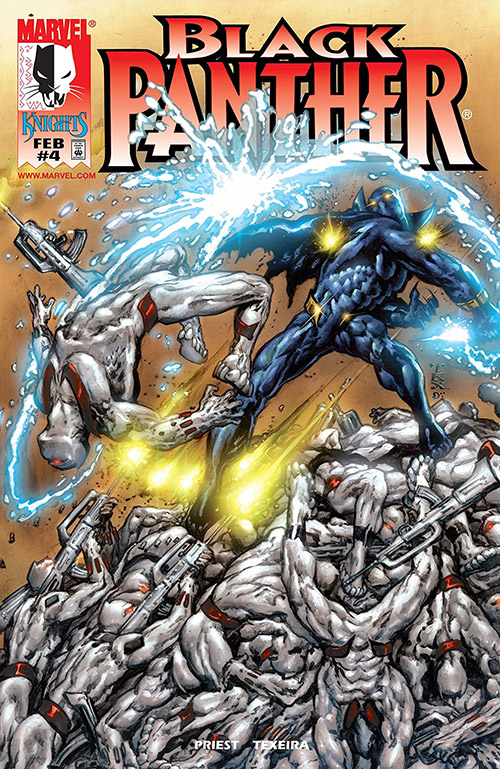

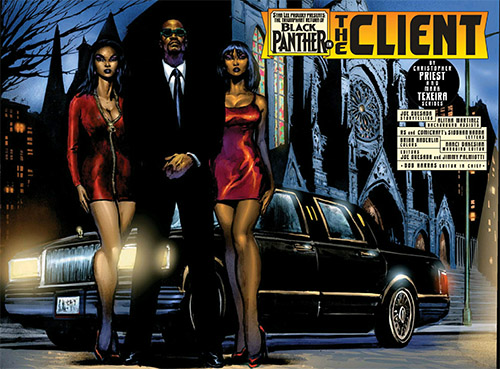

For the majority of the 1990s, Panther continued the pattern of being a guest star in other character’s titles. 1991 did see the return of Jungle Action writer Don McGregor to the character with a new four-part miniseries, this one called Black Panther: Panther’s Prey. Seven years later, Christopher Priest and artist Mark Texeira’s reintroduction of T’Challa arrived. Now considered a definitive take that righted the Black Panther ship, Priest’s era gets mischaracterized as an outright re-imagining. But in truth, the writer looked back in order to create a cohesive mythology. “I love continuity, I love complexity,” Priest reflected back in 2001. “Neither worked very well with [later artist Sal Velluto]’s classic, gorgeous art, which really deserved a lot more room than I gave him. I was also slavishly reverent of past writers Kirby and McGregor and resolutely determined to validate every inch of T’Challa’s previous continuity, which was fun for the fanboys but explaining all that stuff was like New Reader Repellent.”

Christopher Priest’s determination to embrace the past made his additions even more impressive. Panther’s fierce protectors, the Dora Milaje and the Hatut Zeraz, were created during this time, injecting an element of bad-assery to Wakandan lore. “It was great,” Al Ewing says of the 1998 series. “The book read like a noir/crime/spy thriller, with plenty of humor and some cool supernatural touches along the way, starring a sci-fi monarch who was better than Batman.” Ewing doubles-down on that statement, too: “Does the Batmobile have diplomatic plates? I rest my case.”

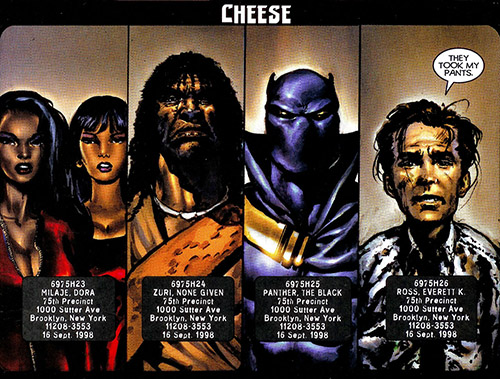

Then there was the character of Everett K. Ross, a quivering, smart-aleck from the State Department who was appointed by President Bill Clinton to escort the Black Panther during his visits to the United States. The book’s framework actually has Ross narrating its ongoing misadventures, keeping T’Challa at arms-length from the reader while simultaneously providing sarcastic observations. “T’Challa is, by necessity, a man of secrecy and cunning, which is difficult to illustrate if he has thought balloons over his head telling the reader everything he’s thinking,” Priest explained in his introduction to his Black Panther trade paperback. “Ross blurted out what many fans were likely thinking, but never dared to so much as commit to paper or post in a newsgroup; questions of race and values and our own insecurity about being super-hero fans well into adulthood. Ross giddily makes salad of all the anxiety of the adult super-hero fan, kicking over many a sacred cow in the process.”

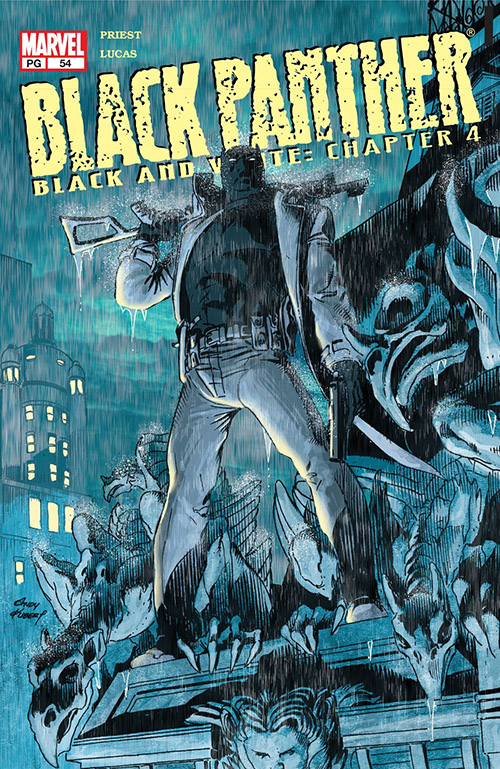

During a period of increasingly edgier Marvel stories, Priest was encouraged by editors Joe Quesada and Jimmy Palmiotti to push the envelope. The time was finally right for a Black Panther completely free of political correctness. “It opened up a floodgate of possibilities for outrageous adventure and gleeful evisceration of some of the most cherished tenets of the Marvel Universe,” continues Priest. “This was how the book achieved its small cult following.” Unfortunately, the marketplace didn’t catch up to the writer’s fan-favorite run until some years later. After experimenting with several different directions, the series was inevitably canceled in 2003. “We began a five year, relentless uphill turd roll trying to get the numbers to move. They never did..”

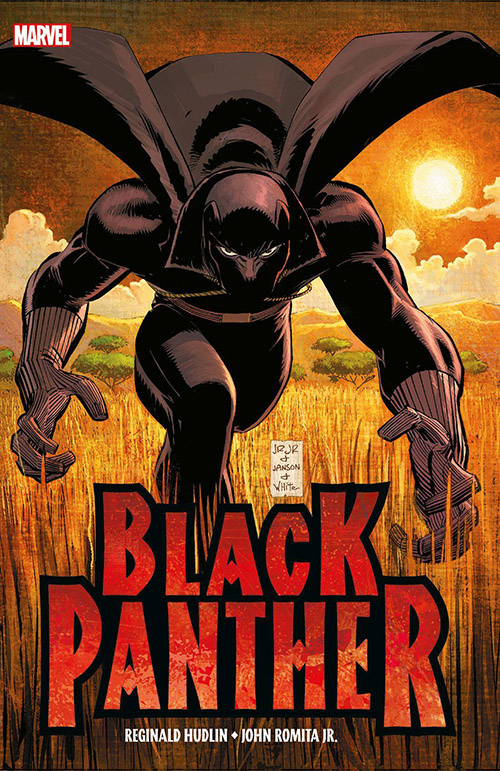

"Who is the Black Panther?" That was the question put forward at the beginning of this article series. It is also the title of Reginald Hudlin’s 2005 opening storyline inside Black Panther #1 (2005). It was a query that Hudlin, the movie director-writer-producer behind House Party, set out to definitively answer during his venture into the realm of comics. With craftsman John Romita, Jr. on art duties, Hudlin’s story begins with a rival tribe attempting to invade Wakanda during the 5th century, quickly establishing how far back the nation has been asserting its dominance. The plot then bounces us forward to experience an earlier version of the Black Panther shrugging off another invasion (by arch-nemesis Ulysses Klaw's ancestor) in the 19th century, followed by a World War II-era smackdown between T’Challa’s elder and Captain America himself (above). All this is meant to set up the book’s main plot: A modern day, coordinated invasion by a not-so-subtle stand-in for The Bush Administration and The Catholic Church. Throughout, “Who is the Black Panther?” is openly reveling in Wakanda’s undefeated streak. You can almost hear Reginald Hudlin cackling with delight as the fictional country advances issue to issue.

The inaugural issue of Hudlin’s run sold out at the distribution level and was immediately rushed to a second printing to meet demand from new and regular comic readers. Some of the credit for this goes to the comics’ multimedia publicity campaign, a rare move not just for a Black-led comic, but comics in general. Black Panther’s profile was raised even higher thanks to Reginald Hudlin. And this wouldn’t be the last time the Django Unchained producer would provide a must-read event for the king of Wakanda...

****

Troy-Jeffrey Allen is the Consumer Marketing Digital Editor for PREVIEWSworld.com and Diamond's pop culture network of sites. His comics work includes BAMN, Fight of the Century, and the Harvey Award-nominated District Comics.