Myth Makers: Comic Creators On Black Panther - Part 1

Feb 18, 2018

by Troy-Jeffrey Allen

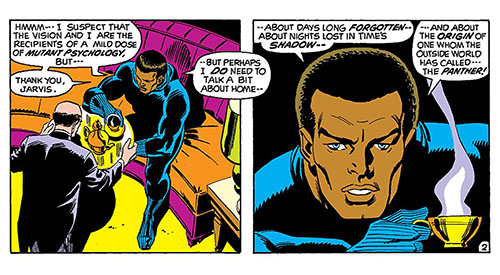

For a character that’s been around for 52 years, Marvel’s Black Panther is not an easy one to pigeonhole. Yes, he’s an African king, but, unlike the rest of his Marvel contemporaries, he’s rarely been depicted as visibly distressed or brash. If anything, since his debut in 1966, the Black Panther has largely been depicted as guarded, evasive, and mysterious. For a visual medium like comics, this makes a lot of sense. The name “Black Panther” automatically suggests a predator that slinks around ominously before attacking. Couple that with the fact that he is a ruler and you get a very reserved personality who rarely vocalizes his anxieties, only communicates with purpose, and is very economical with his words.

Still, the story behind the Black Panther’s development throughout the years isn’t quite as calculated as King T’Challa himself. Many creators have provided layers to the Black Panther. Each additional coat helped build a mythology that has culminated in the character’s first cinematic debut. But Hollywood has a tendency to repurpose works of fiction (and fact) to fit their three-act structures. Which lead PREVIEWSworld to ask those who have worked on the Black Panther in comic books – his true and original format - “Who is the Black Panther?”

“He’s a bonafide cultural force in the Marvel Universe,” current Marvel writer Al Ewing says, reminding us that the character is a political figure in his fictional world. Ewing sees the undeniable link between T’Challa and Wakanda – his African kingdom – as his actual superpower. “Thanks to the writers and artists who’ve worked their magic on the character down the years, Wakanda’s become a complex region with history, geography, and a believable political landscape, that exerts itself geopolitically on the wider world.”

Ewing wrote the character back in 2015 for his fan-favorite and critically lauded The Ultimates series. The book’s plot centered on Panther and a seemingly incongruous line-up of heroes attempting to fix the cosmic problems of the Marvel universe. “The idea was always that The Ultimates was the most powerful team going,” Ewing explains. “Every world leader, at any time, has one eye on T’Challa. That’s real power, and it was the kind of power we needed to round out The Ultimates.”

Ewing’s interpretation made it a point to invite the Black Panther’s sovereignty into his ongoing adventures, but other creators saw those superheroics as less of a priority. “That’s another reason we didn’t use him regularly…he’s the king of a whole freaking country,” former Avengers writer Kurt Busiek told us. Busiek suggests that Wakanda’s head of state would be negligent in his duties if he continuously dropped everything to team-up with other Marvel heroes. “He doesn’t have time to hang out in New York and tackle Avengers missions. He’ll help out when he’s needed, but there’s a lot on his plate,” he concludes.

Kurt Busiek’s time on The Avengers started in the late 1990s, nearly three decades after the team and Panther originally debuted. Immediately prior to Busiek coming on (with artist George Perez) the Avengers had gone through so many roster changes that it was time to make the Avengers feel like -- well, the Avengers again. That included bringing T’Challa back into the fold. “He’s one of the classic Avengers, for sure,” affirms Busiek. “We didn’t use him regularly, in part because he was busy doing stuff in his own series and Avengers already had a lot of other-series continuity to juggle.”

The Harvey and Eisner Award-winning Busiek had to split Black Panther’s time with Christopher Priest, a former Marvel intern-turned-writer whose 5-year run looms large over the character. “Christopher Priest was writing his solo series, so I was guided by that in that I wanted readers of both books to feel like they were reading the same character.” The Panther having dueling narratives at the same time was a bit of a rare occurrence for the superhero. Seldom did he experience enough popularity to warrant such editorial attention. If anything, for decades, the Panther had more of a cult status in comics. His visibility usually increased depending on what was happening in the zeitgeist at the time. As a matter of fact, it could be said that his very existence stemmed from a cultural sea change in America.

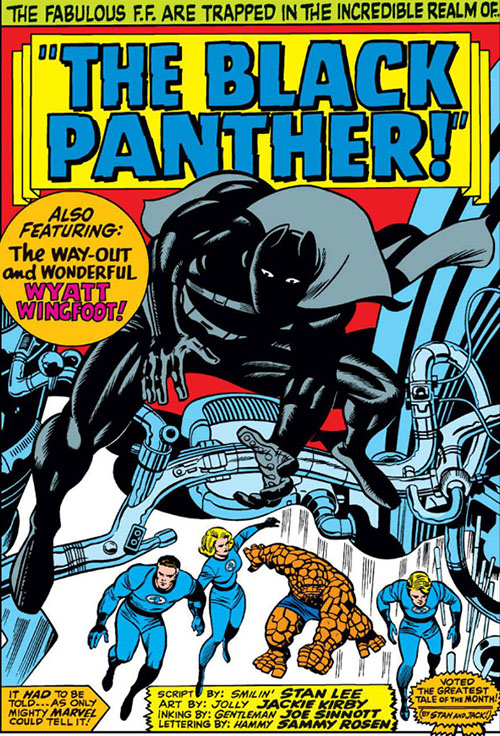

“It had to be told -- as only mighty Marvel could tell it,” Stan Lee gloats on the first page of 1966’s Fantastic Four #52, the first appearance of the Black Panther. Artist Jack Kirby depicted a giant-sized Black Panther mysteriously and ominously looming over the Fantastic Four: His piercing eyes somehow fixated on them and the reader at the same time. This imagery dupes any looking at it into assuming T’Challa is a foe of Marvel's first family. In actuality, he’s luring them into a game of cat-&-mouse for reasons that the reader would have to discover. From the very moment he was introduced to the world, T’Challa was enigmatic – a mystery before he even uttered a single line of dialogue.

Fantastic Four #52 is pure subversion on the part of both Lee and Kirby. Deliberately, these notoriously combative collaborators still managed to function as a unit long enough to throw your expectations off. They are banking on reader ignorance. They want you to assume that the dark-skinned mystery man is evil just so they can upturn the whole thing. It’s not until the last three panels of the issue that we discover that the Panther is not the super-villain of the week. That his ominous attire is a symbol of “Panther Power”, that he is perhaps “the richest man in all the world”, and that T'Challa is African.

The push for national civility had long kicked off by the time the Black Panther arrived in 1966. For white Americans, these movements across the United States forced them to no longer deny the presence of racism. Through the media, Americans faced images of slain activists and dogs attacking non-violent protestors. People of color were visible and marching for public accommodation or conscientiously objecting to the draft. Because of these things, the Black Panther’s debut was more of an imperative. T’Challa wasn't the first Black Marvel character, but he was the first to embrace the disruption of the day. In his first appearance, you can see that he has the fearless dexterity of Muhammed Ali, the authoritative glare of Sidney Poitier, and the dignified delivery of MLK – all very visible Black men of the time. Even the way he talks about the source of his “Panther Power” feels like it was cribbed from mid-1960s sloganing.

What Lee and Kirby created was room. An opportunity. Still, despite providing the Panther with multiple guest appearances in a slew of Marvel books, it was up to the artists and writers that came after to find the things that made T’Challa his own man.

“One day Stan called me in, handing me an already penciled issue, and said, in essence, ‘From now on you’re the Avengers writer,’” recalls former Marvel editor-writer Roy Thomas. And with that, Thomas went from writing Millie The Model to taking over Avengers from Stan Lee.

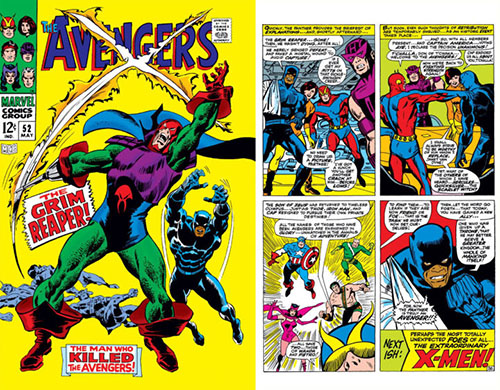

Thomas’ first issue – Avengers #35 – didn’t contain a single Black Panther appearance but the Wakandan would officially join the team on Thomas’ watch starting with #52. “That was Stan’s idea,” Thomas recalls. “The only thing I didn’t like was that after [artist John] Buscema had penciled the issue, Stan decided that the Panther’s head had to be redrawn throughout so his lower face showed. I presume he realized that, if he ran around in costume with the Avengers all the time, people wouldn’t be aware of his ethnic origins.” Despite no longer writing the series, costume alterations wouldn’t be the end of Lee’s tweaking. “There was the period during which Stan decided he would be called Black Leopard. This was all to avoid confusion with the Black Panther Party.”

Only a few months after T’Challa’s introduction to the comic world, Dr. Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale co-founded the “Black Panther Party for Self Defense” in Oakland, proving that ideas are simply in the ether and are just waiting for someone to utilize them. As a matter of fact, segments of the 2018 Black Panther film knowingly takes place in Oakland (a connection that director Ryan Coogler – who is also from the California city – has been open about). The boldness of the BPP did not go unnoticed by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. The Federal Bureau of Investigation was eager to label the Panther Party as domestic terrorists, communists, and a “hate-type organization”. The description took hold of white America, resulting in an increased institutional backlash from law enforcement.

This narrative would once again cause an off-panel identity crisis for T’Challa. The Marvel bullpen was suddenly compelled to react to the zeitgeist. Only this time, it wasn’t to build Black Panther but to take elements away from him.

“Marvel higher-ups got worried after the Oakland Black Panthers got prominent,” explains Steve Englehart, the writer who followed Roy Thomas on The Avengers comics. “I remember hearing ‘panthers and leopards are more or less the same’ – but there was no logic to it for the character, and the public liked ‘Panther’ better than ‘Leopard’ so [they] switched back. “It was just an unfortunate juxtaposition of circumstances that both Black Panthers emerged at roughly the same time,” Roy Thomas adds.

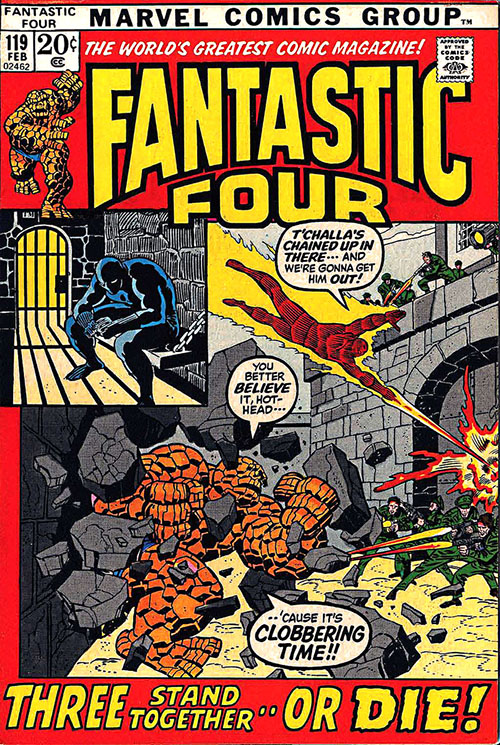

Eventually, these links between the Marvel character and real world events would become more defining. As Thomas began writing Fantastic Four he invited T’Challa to return to the book that introduced him to the world. Most notably, in a tale that used a fictional place to talk about racial segregation. “In 1972 there was an issue of FF where T’Challa was imprisoned in Rudyarda, the fictional country in the Marvel Universe that passes for South Africa,” Black Panther writer Jonathan Maberry recollects. “Ben Grimm and Johnny Storm go and help break him out. I showed that issue to my middle school librarian and asked if anything like that ever really happened. She gaped at me and asked if I’d ever heard of Apartheid. I had not.”

A fan of the character since his youth, Jonathan Maberry is a Bram Stoker award-winning writer who finally had the chance to tell his own Black Panther story in 2009. “I’m old school with the Panther, I began reading comics with Fantastic Four #66,” Maberry proudly states.

It’s Maberry’s personal story about T’Challa that really characterizes Panther for him. “My father ran the local chapter of the KKK. There were absolutely no people of color anywhere in our neighborhood, or school, or anywhere. When I encountered T’Challa in the pages of the Fantastic Four comic it felt like something even more fantastical than superheroes or space aliens.” Because of his upbringing, the author’s exposure to Black Panther was a lightning bolt. “When I showed the comic to my father, he tore it up and belted me across the chops,” continues Jonathan. “Aside from being a racist, he was also a child abuser and criminal,” he adds. “It’s fair to say that T’Challa saved my life. Because of that character – a comic book character – I learned to see the world more as it really was than what I was told it was. Within weeks I had enrolled in a martial arts school in what my father would call a ‘ghetto’, meaning a black neighborhood. I made my first friends of color, and from there my course diverged greatly.”

In Part 2 of "Myth Makers": The man who defined the character for the 1970s and T’Challa vs. the Ku Klux Klan.

****

Troy-Jeffrey Allen is the Consumer Marketing Digital Editor for PREVIEWSworld.com and Diamond's pop culture network of sites. His comics work includes BAMN, Fight of the Century, and the Harvey Award-nominated District Comics