For Harvey, Comics, and Cleveland — The Joyce Brabner Interview

Dec 01, 2011

|

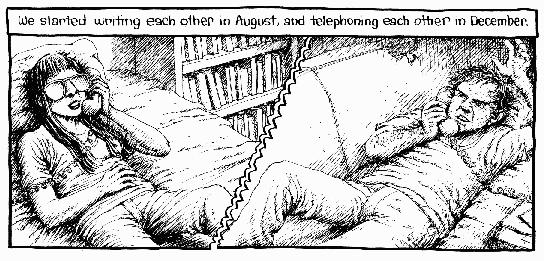

Joyce Brabner has been around comics — and reading — for a majority of her life. And it was her love of reading which eventually lead her to contact Harvey Pekar by mail when her comic shop sold out of the latest issue of American Splendor before she could read it.

They grew closer through their correspondence, and when they eventually met face-to-face, they knew the next day that they should marry. And did. On their third date.

They grew closer through their correspondence, and when they eventually met face-to-face, they knew the next day that they should marry. And did. On their third date.

Over the years, in between writer various politically-charged comics projects and contributing her time and energy to various social programs and cause, Joyce also worked with Harvey on American Splendor, working behind the scenes on the series as well as playing a character in the series itself.

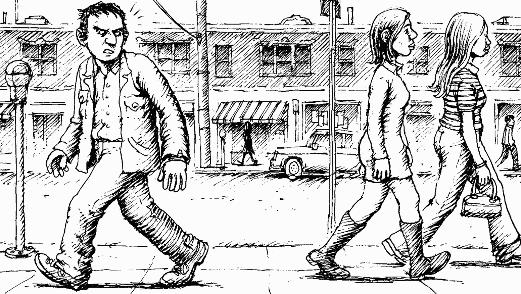

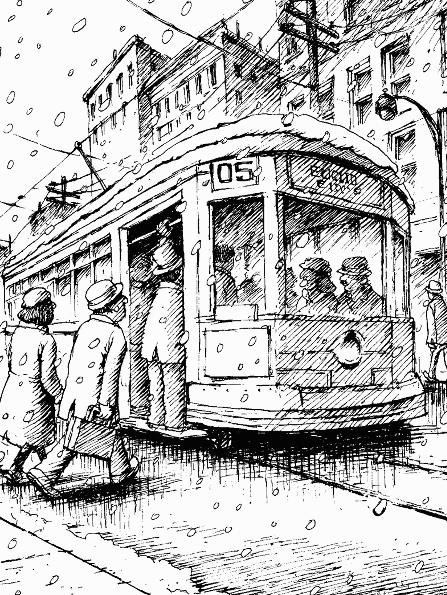

Harvey Pekar's Cleveland is one of Harvey Pekar’s final projects; a love letter of sorts to the city he called home, as well as an autobiographical record of his years in the city, with Joyce. As the publication of Harvey Pekar's Cleveland nears, Joyce was kind enough to sit down and talk with us about what could be Harvey’s most personal project, and Joyce’s own project to build a lasting monument to her late husband.

PREVIEWS (P): What will American Splendor fans, and those new to Harvey Pekar's work, find unique about Harvey Pekar's Cleveland?

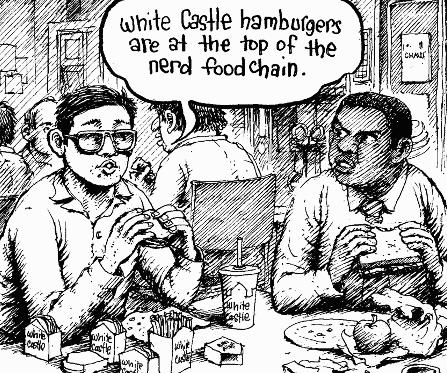

Joyce Brabner (JB): Well, it shows off the prowess of an extraordinary young artist, someone Harvey was tremendously excited about working with. From the very start there were other people who wanted in on the book — some rather aggressively — and Harvey said “no way.” He had absolute confidence in Joseph Remnant’s ability to do this, which was interesting, because Harvey could have chosen artists who live now or have lived in Cleveland. We think that Joseph was able to get into Harvey’s world, the way Harvey saw the city, which was a lot more important than just living there. Actually, in a way, it is probably an advantage he did this long distance, because he paid more attention to Harvey. This is a book about Harvey’s history with Cleveland, so to speak; his relationship with Cleveland. I find myself telling people that it is kind of a love letter to a thing that meant so much to Harvey. But this is not putting a shine on the city, yet it is certainly not “let’s trash the hometown.” You got to look at Harvey’s relationship history. I’m his third wife. The book is also about that we had better talk about "where we're going in this relationship" thing, too.

Joyce Brabner (JB): Well, it shows off the prowess of an extraordinary young artist, someone Harvey was tremendously excited about working with. From the very start there were other people who wanted in on the book — some rather aggressively — and Harvey said “no way.” He had absolute confidence in Joseph Remnant’s ability to do this, which was interesting, because Harvey could have chosen artists who live now or have lived in Cleveland. We think that Joseph was able to get into Harvey’s world, the way Harvey saw the city, which was a lot more important than just living there. Actually, in a way, it is probably an advantage he did this long distance, because he paid more attention to Harvey. This is a book about Harvey’s history with Cleveland, so to speak; his relationship with Cleveland. I find myself telling people that it is kind of a love letter to a thing that meant so much to Harvey. But this is not putting a shine on the city, yet it is certainly not “let’s trash the hometown.” You got to look at Harvey’s relationship history. I’m his third wife. The book is also about that we had better talk about "where we're going in this relationship" thing, too.

It’s very clear how he sees his life in the city, and it finally answers the question once and for all why a writer of Harvey’s caliber would choose to stay in a city like Cleveland. When we got married, I left a really sweet deal. I had a job that was created for me at my request by the governor of the state, doing exactly what I wanted. I had friends with a small theater/studio... you know, good people. Lovely. I offered Harvey the chance to A) pick everything up and I’d support him and he can just write full time or B) there’s the V.A. hospital down the street. He could not let go of it. It was not a lack of adventure. It was not any type of cowardice. This was just the place; he could not separate it from his identity. So he sort of sold me on the city, showed me a lot of things I was looking for and, of course, I was in love with him. So I came out here. I came to Cleveland and there you go.

P: Both Harvey Pekar's comics and your own focus on real people and real world situations. Whether exploring the mundane details of daily life or describing political topics, what is the importance of showcasing "the real" in comics? Why use comics specifically to do this?

P: Both Harvey Pekar's comics and your own focus on real people and real world situations. Whether exploring the mundane details of daily life or describing political topics, what is the importance of showcasing "the real" in comics? Why use comics specifically to do this?

JB: Well, since I have done so many public appearances with Harvey, and I am probably the expert on what Harvey thought or meant or whatever, I’ll answer this. I have heard him asked this question, and part of my responsibility is to make sure his voice, even though he is not here right now, is amplified. He would say he could never really imagine not writing about himself. It’s not that he was an egotist, it is just that he did not have an imagination that ran that way. Sometimes he would joke that he had so much trouble understanding other people. That made people think was he just so anti-social he could not relate. That’s not true, because so many of his books were stories that he wrote, where he was retelling someone else’s story. He wrote about the real stuff, and this is what we had in common since the moment we met. I am someone who has kept a diary since I was a kid, and I taught diary writing. I taught diary writing to guys at maximum security prisons that would only get out for a half hour from their single cells to be with the other population to eat.

What I found, is that a life observed, where you have to answer to a blank piece of paper with a pencil, makes you look for what is worth writing about. In fact, I tell my guys at the joint — it was played for comic effect in the American Splendor movie — but I tell my guys in the joint, “I want you to write something to fill up these notebooks, and if your life is not worth writing about, then they have already gotten to you, they won.”

This diary tradition of literature goes back to the “Court Ladies” of Heian period of Japan. These were women who wrote diaries, who were not allowed to go outside their room or the building. Like Anne Frank, they’d write about a leaf changing color or a tree outside their window. It would have so much more meaning because of the slowing down and observing. I think Harvey found that watching for stories, listening for stories, made him feel much more alive, and I think it comes through in the writing. Did Harvey like Fantasy or Super Heroes or stuff like that? Certainly as a kid, God knows, yes. Even as an adult, in limited quantities, for him those were occasional flavoring; he could not do a steady diet of it. It was not as though they were junk food. It just wasn’t his dietary preference.

P: Harvey Pekar's Cleveland is part autobiography and part history. How does the wider context of the history of Cleveland inform the autobiographical parts?

JB: Read the book and see if he pulled it off.

P: This book should further illuminate the deep connection between Harvey Pekar and the city of Cleveland. You have also been involved in efforts to erect a memorial statue in Cleveland for Harvey. What can you tell us about that? And is there anything our readers can do to help with the project?

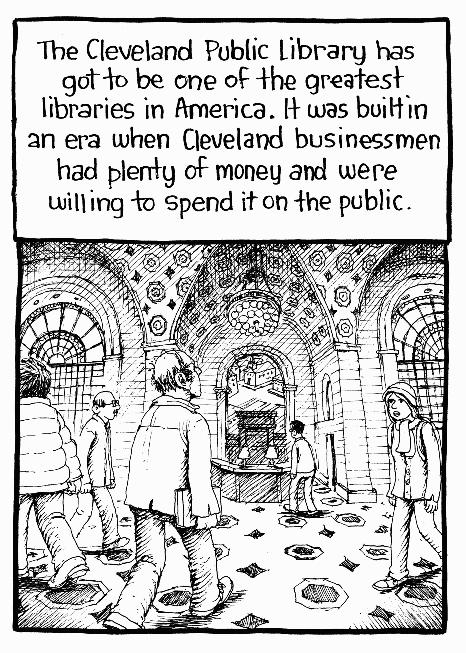

JB: They can contact me directly at harvey.pekar.estate@gmail.com. One of the most important places to Harvey, and to me, is our Cleveland Public Library System, which is just amazing. I don’t know what the numbers are, but we’re in the top 4 or 5 Library systems across the country. We were both people who grew up saved because of libraries.

JB: They can contact me directly at harvey.pekar.estate@gmail.com. One of the most important places to Harvey, and to me, is our Cleveland Public Library System, which is just amazing. I don’t know what the numbers are, but we’re in the top 4 or 5 Library systems across the country. We were both people who grew up saved because of libraries.

I suppose you could say that the memorial would enhance Harvey’s reputation. I don’t care about that… he doesn’t need to be reassured that he is important anymore. I think this is a chance to show people, for people to vote with their small donations to show other people, that comics are art and literature, and that is why it is called the “Harvey Pekar Comix as Art and Literature Memorial Statue/Library Desk.” Rather then put it on a giant granite block that would have doubled the cost of the project, we are making this into an actual desk where people can sit. There are things in the drawer that Harvey used to write with. Comics are words and pictures and you can do any anything with words and pictures. I saw a statue of the Michelin Man. We have statues of Greek Gods at the post office. I don’t think there are very many comix-related statues in the world, and if there are, I wouldn’t be surprised if most of those are tied into cartoons like Mickey Mouse and Disney stuff — I am talking about comics as art and literature. Not comics as I-can-wrap-a-fish-in-it-after-I-read-it entertainment. It’s kind of embarrassing to use lofty phrases like “elevate the art form...” If this flies, why not do a statue in the library or hometown of somebody else. In Ohio, there is the Thurber House, and a lot of illustrators or cartoon people came from around here, but I am not about to turn my house into the “Pekar House.” They spelled Siegel’s name wrong on the plaque for the Siegel and Shuster house, which thrilled everyone after it got stolen as they could replace with one properly spelled.

If this doesn’t work with Harvey attached to it, maybe someday someone will have enough juice to make one about comics. But if the project is overfunded by the time this hits print — sometimes people get enthusiastic on Kickstarter — and once all the expenses are covered, we have made arrangements to use the funds to put more comics in the library. The idea is to create a library that is a magnet for comic book readers, not scholars. Not the guys who go with white gloves to a facility and unfold with reverence some Little Nemo page or watches as it is unfolded in front of them. I mean, come in, stick your nose in a comic and read it. Sit at the desk which we will always keep supplied with pencils and paper. Draw your own words and pictures or draw on the statue because the back of it is going to be slate, arranged like the kind of storyboards Harvey drew. So if you want to still get involved we got a good use for the money.

P: You're also interested in "paying it forward" from what we've learned. How do plan on helping new writers/artists to the comics industry?

JB: I am going to focus on the writers. Because I am a comic writer and I have only published very few comics. Everyone assumes that the artist should get a whole lot more money and credit than the writer because they put in so much work. For some books, Yes, and some books, No. The research Alan Moore and I did for Brought to Light was quite hefty, while the art came out a lot faster. There is a big cost to making comics — and I don’t want to hear about just putting it online. A big expense is printing and binding. And I have been extremely disturbed by this trend of sending our comics to be printed in China because they can save a few bucks, and then congratulating ourselves for publishing comics that are sensitive to the needs of the working man or poor people. Or sending our comics to be printed across Lake Erie into Canada. Well, their industry is subsidized by the government. They have the resources; they’ve got the trees as crops. I want to make the city of Cleveland a comics Magnet — first with the comics-friendly library, then with the history.

|

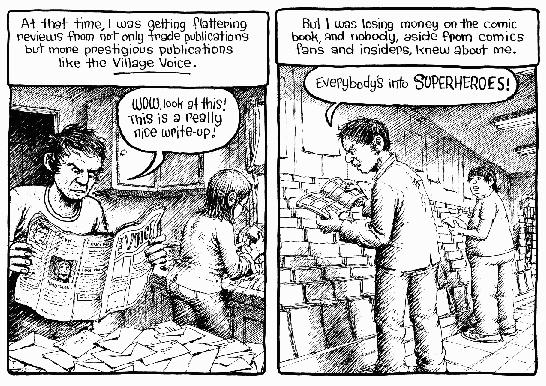

Superman was invented practically around the corner from where Harvey lived. I want to keep people in my hometown making comics and working with people who get comics, who are not afraid to take chances on the printing and not afraid to put there money where their mouth is. What I want to do is to give somebody out there something Harvey needed and something I needed at a particular point in our careers: the means to publish, distribute and write comics for somebody at the beginner-level, who has not yet published. We’re still working out the details. I would love to have a convention or festival or something pick up on it or, of course, we could run it out of a library. The first person I will be calling when this is over is Peter Laird, and try to get him to tell me what did work and what did not with the Xeric. I am not trying to replace the Xeric, I just think comic book writers have a unique problem in the business whether it be coaxing or cajoling someone to draw, or in Harvey’s case, taking a whole bunch of odd jobs to be able to pay an artist. The artist got paid even when Harvey didn’t. Harvey wasn’t getting paid for comics for years and years and years. It wasn’t ’til after he married me that he was able to put any money back in his pocket. One year, he made $500 on American Splendor. Or the other problems writers have now, that I have experienced with He Who Shall Not Be Named, is “where is my artist, and will he please finish the damn work! because I want this book I wrote that everyone is so excited about to come out. Plus, I don’t get my last check until he is done."

Also, I am going to mentor. If anyone has anything they want to learn from me, or if they want to learn about Harvey. There is something else I am writing, where I am going to be talking to people who were influenced by Harvey and to demonstrate how that worked, not to just shine his halo, but create a manual of creativity, Harvey’s way. If one more person says “there will never be another Harvey Pekar” — well we already know from the movie that there have been other Harvey Pekars, and Harvey would not have believed in this medium if he thought that only a few rarified folks could do it. There have been other people he would be really proud to read and enjoy reading. So I am going to go to the writers and please, dear God, send me to seminars and colleges and things like that, because I got such a kick out of doing a thing at the Purdue oncology center. They spent a whole semester studying Our Cancer Year. I went down there and worked with people who were in treatment for cancer, people who were studying for the medical professions — different artists and writers who created their own Our Cancer Year-type books.

P: How have independent comics changed since you first became involved with them? How did the process of publishing Cleveland differ from earlier efforts?

JB: Well the first thing that I think has happened is they are getting physically smaller. Okay, remember now in Harvey’s case, because he was working with wet printing, he was working with a thing the size of an unfolded newspaper. These original newsprint American Splendor are prizes to Kickstarter donors in certain reward categories. Harvey was real impressed when he saw his first mini comic, by Matt Feazell, and he loved that. Probably because the book looked like something Harvey did with stick figures. So he recognized a kindred spirit. There has been a lot of experimentation in form and content, which probably has to do with the rise of ’zines.

P: How did the process of publishing Cleveland differ from earlier efforts?

JB: Well, the big difference was Harvey got paid an advance against royalties. He got paid. Something kind of tangential and related to this is something I said on the Kickstarter page. When you’re 25, it might be selling out, but when you’re our age, it is called getting paid for what you do.

P: Do you think comics have earned the right to be called "graphic literature"?

JB: I suppose if graphic means they have pictures, we’re probably safe with that. Literature. I have never found a suitable definition for literature. If its crap, they can still call it genre literature. [Laughs]

Comics earned the right to be respected and looked at and enjoyed, what can I say. I fell in love with a guy whose life I met through comics. So for me, it is like a no-brainer; I married into it. I changed all my plans; I gave up my government job because I believed in Harvey and because I believed in the medium. Because I like chances, a little bell went off in the back of my head and said “go, jump, do it.”

P: What are some of your favorite "graphic lit" titles?

JB: Now what do I like to read? I like to read anything somebody’s put their heart into, because I am one of these people who would rather have a real simple... okay, I visited other countries and have friends who have not had much money, and I would rather have a real simple meal prepared by them, where they put their heart into it.... I mean we had exotic meals at Cannes and stuff like that. There is something about the noodles and the beans dish that somebody prepares for you. I guess I am thinking a lot about food because I was hanging out with Tony Bourdain last night. He is a doll.

JB: Now what do I like to read? I like to read anything somebody’s put their heart into, because I am one of these people who would rather have a real simple... okay, I visited other countries and have friends who have not had much money, and I would rather have a real simple meal prepared by them, where they put their heart into it.... I mean we had exotic meals at Cannes and stuff like that. There is something about the noodles and the beans dish that somebody prepares for you. I guess I am thinking a lot about food because I was hanging out with Tony Bourdain last night. He is a doll.

Anyway, one of the places I love to get books from is Microcosm Publishing. They publish personal ’zines, little tiny things that anybody can do. The kind of stuff you would find at SPX, which is why I love SPX. You’ll find a comic book about what it is like to be a black ghetto girl lesbian who loves heavy metal music and you can’t figure out what kind of shoes you’re supposed to wear… something like that. I will find that every bit as fascinating and unique as somebody’s story about a so-called larger thing. That said, I do love people who can pull off the writing and observation and illustration. So obviously that means I like Allison Bechdel. I have always loved Dykes to Watch Out For, and Fun Home is terrific. Something that nobody knows about me, is that I was reading before I was three, and when your little your eye muscles don’t really work that well, being able to follow small print on a page without illustrations, you know it hurts your head to look at a normal text book. I made the jump from Cat in the Hat to Nancy Drew books because when I was 5 or 6, somebody gave me some Nancy Drew books and I was very disappointed because they only had one picture and tiny words, and I thought they were grown-up books. I had a cousin with a comic collection, and I realized the words were the same size as the Nancy Drew book. So I went back and I tackled my first Nancy Drew book, and realized I could read. So, comics really encouraged me to read more serious literature. I like those dumb old DC comics with Jimmy Olsen as Porcupine Boy or Matter Eater Lad from the Legion of Super-Heroes. Linda Lee’s robots hiding in trees… anything drawn by Curt Swan or Wayne Boring. It is a nostalgic thing, but it is something that I find pretty comforting because it makes me think about lying under the rug with my cousin, hiding. We both agreed we would grow up and live together as hermits.

|

I just think those comics should be printed in black-and-white or priced to the point where kids can read them. Early on, when I was doing the whole Brought to Light promotion tour, I met Fred Hembeck, and I said “Look, you’ve got to draw me a picture of Lois Lane stalking Superman,” because that was total womanhood to me when I was six. I really loved any of the illustrations in the Oz books. But the reason I gave up comics was that I was reading them so fast I would go through like six a day and I was chewing through books the way we did when we were kids, and then have a massive headache. For 20 cents I could actually get the bus to the public library so I would not exhaust myself carrying things back. I would have to read the spinner rack at the Grocery store and get chased out of there for that!

*Joyce Brabner photo courtesy of Seth Kushner. Art by Joseph Remnant.